Lost Marbles

Project number: 006

Year: 2016

Type: Research

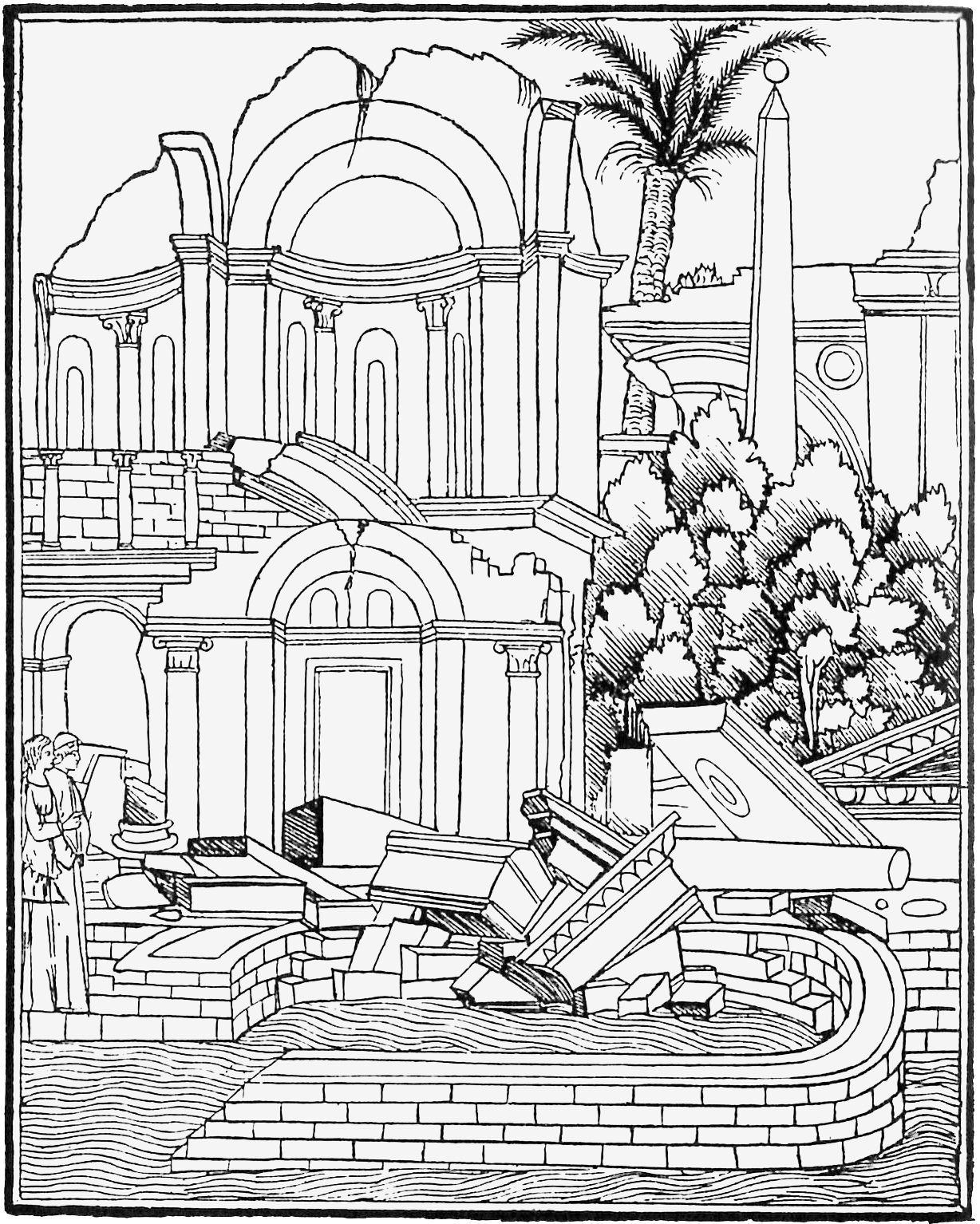

The Lost Marbles project started in 2018. The inspiration for the research came after reading a book called Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. The book was printed in 1499 in Venice by Aldus Manutius. Scholars still question who the author is. The book became an inspiration for this research and inspiration, in general, because it explores architecture from the point of view of the extravagant and the exuberant. It explores architecture and beauty from the point of view of indulgence in a context where things are judged not on their functional necessity or utilitarian value but rather on their meaning and beauty. Insinuating that architecture does not have to be useful to be important. The description of different marbles and their place in antiquity is a significant part of the book. Having read such a vivid description of the importance and beauty of these stones triggered a wish to explore and find Scandinavian marble, mainly focused on the Norwegian context.

Norway has a wealth of different marble; however, it never had an empire with the ambition or the wealth to extract the marble for architectural purposes. However, traces of Norwegian marble can be found on several public buildings. As we learned later, many quarries used to extract marble for these projects are now shut down or abandoned. Although sometimes, with all the industrial infrastructure still in place. One of the great discoveries of the study was that much of the most exciting and colorful marble was no longer quarried. After reaching out, talking to the land owners, and visiting the abandoned quarries, our main feedback was that continuing the quarry operation had become financially infeasible. In many of these abandoned quarries, beautiful marble in all colors was lying around in the landscape.

Another discovery that proved essential came after interviewing researchers at the GEO (Institutt for Geovitenskap, Universitetet i Bergen) was that stones that were highly valued and used for the most precious sculptures in Roman and Egyptian antiquity, such as Porphyry, were being quarried on an industrial scale in Norway only to be crushed and used as gravel. The process often used in the quarrying process was dynamite. Such incredible brutish use of a stunning stone gives urgency to how we can better use our natural resources. Although the research started as an intuitive fascination with the material, investigating the subject revealed how our use and misuse of marble reflects deeper structural problems relating to the use and abuse of resources.

The most aesthetically pleasing experience of the study came while looking for a green marble called Modum Serpentinite. We went into the forest looking for the quarry, with little expectations of what to find other than that we were looking for a quarry somewhere in the forest with much green stone. We rented a little Toyota that took some heavy beating in that forest. It was pouring rain. At some point, there was no more road. We got out of the car and started walking. After walking soaking wet for a while, the road lit up. A fluorescent green light sparked from beside the road as if we had found a hidden treasure full of jewels. The stone was a type of serpentinite that had a distinctly fluorescent appearance. It was magical. The magic consisted of the intensity of discovering a stone together with its natural habitat. To see the correlation between the color nuances of the stone and how they matched the surrounding forest. At that moment, the story of the spectacle was intact. The logic of the material and its origin came together in one spatial experience.

Photo / Modum Serpentinite. Quarried at Modum, Norway.

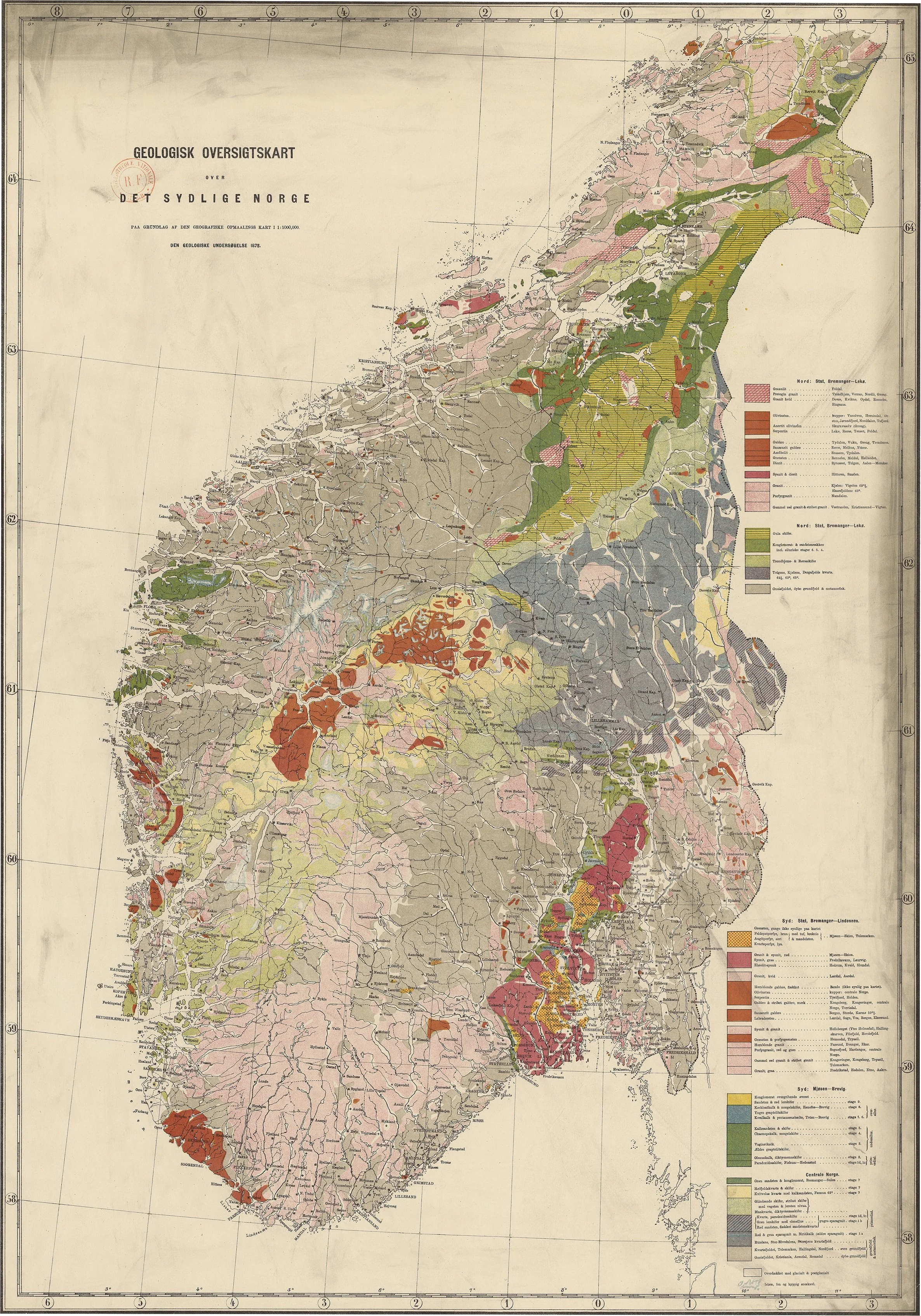

Geological map of southern Norway.

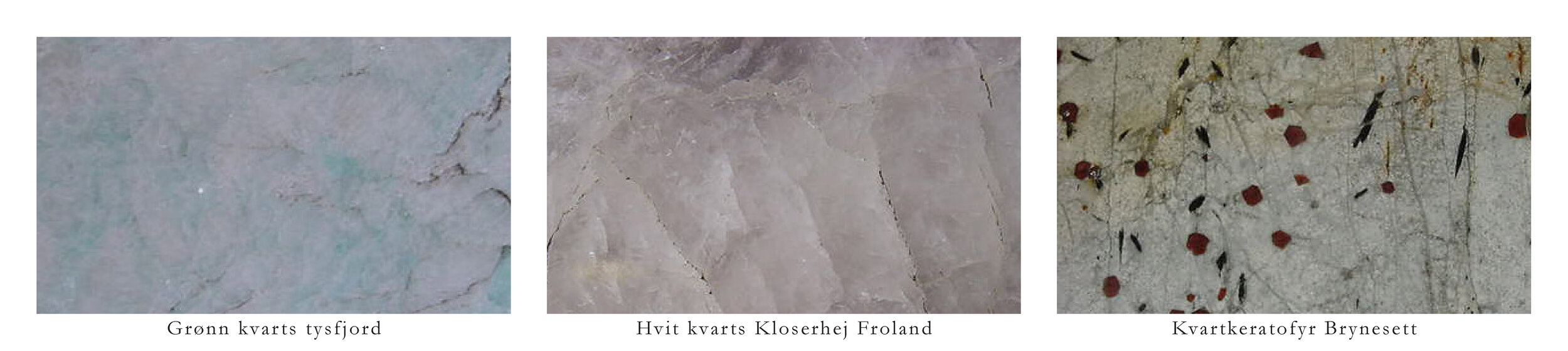

Extracted page from Marble Atlas.

Extracted page from Marble Atlas.

Extracted page from Marble Atlas.

Extracted page from Marble Atlas.

Extracted page from Marble Atlas.

Extracted page from Marble Atlas.

Extracted page from Marble Atlas.

Illustration from Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.